“Ask not what your country can do for you,

ask what you can do for your country.”

That sentence, spoken by President John Kennedy in a famous speech, is a good example of chiasmus, a rhetorical figure that reverses the terms of the two clauses that make up a sentence, or a part of a sentence.

Chiasmus is thus a linguistic twist or turn that you can use to express a crosswise mode of thought. Chiasmus (ky-AZ-mus) means “a crossing,” from the Greek letter chi, X, a cross. You “cross” the terms of one clause by reversing their order in the next.1

The Greek letter chi ( X ), the initial letter of chiasmus, is my symbol for chiasmic2 structures, or crosswise modes of thinking and expression. A famous line from “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” a poem by John Keats, can be represented as:

beauty is truth

X

truth [is] beauty

Matthew 19:30 states a simple chiasmus: “But many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first.”

first shall be last

X

last shall be first

Indeed, the Bible shows the concept of chiasmus as evolving into structural forms of ever increasing beauty and complexity. For example, take note of the structure of 1 John 4:7-8:

Beloved, let us love one another.

A For love is of God

B and whoever loves is born of God and knows God

B He who does not love has not known God

A for God is love.

And from the book of Amos:

A Seek ye me, and ye shall live.

B But seek not after Bethel,

C Nor enter into Gilgal,

D And pass not to Beer-sheba:

C’ For Gilgal shall surely go into captivity,

B’ And Bethel shall come to naught.

A’ Seek Yahweh, and ye shall live.

(Amos 5:4b-6a)

If you compare the first and last lines, and so on, you will see that the italicized words reflect parallel correspondences in this A-B-C-D-C’-B’-A’ chiasmus. A and A’ are what may be called “thought-rhymes,” as are B and B’, and C and C’.

Some chiasmic structures in the Bible are marvels of complexity. The Gospel of John is a good example. Not only are there, throughout John’s Gospel, many chiasmic units nested one within the other, but the book itself, as a whole, is a complex interlocking chiasmus that goes so far beyond the ordinary sense of chiasmus that it must be called a meta-chiasmus.

In this book I will explore the concept of chiasmus not only as a figure of speech but also, and more importantly, as a figure of thought and a figure of reality. The book will show how the concept can be generalized beyond its literary meaning and that chiasmus, and the way it turns things around, is a powerful conceptual tool that enhances the poetics of perception.

Chiasmus, in its literary expression, varies greatly in beauty and complexity and, as the complexity increases, there comes a sense, or intimation, that the concept can be even further generalized. Consider these examples:

Chiasmus 101

The shortest chiasmus I’ve found is a clever play on words, in Latin, that tells the tale of Eve, the first woman in the Garden of Eden, and Mary, the mother of Jesus. Using three letters only, crisscrossed, it reveals the reversal (Christian Theology 101) whereby Mary becomes the new Eve:

Eva X Ave

Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum . . .

Another example on the freshman level is a children’s song we all have sung:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

X

a merry old soul was he

To more clearly show the inverse parallelism, it can also be expressed as follows:

A Old King Cole was

B a merry old soul

B a merry old soul

A’ was he

The chiasmic structure is A-B-B-A’.

Chiasmus 202

Some examples with a slight increase in complexity:

The concrete without the universal becomes trivial. The universal without the concrete becomes irrelevant. — Alfred North Whitehead

All that is is in God . . . and . . . God is in all that is. — Hyatt Carter

A succession of feelings, in and of itself, is not a feeling of succession. — William James

Chiasmus 303

Two by philosopher A. E. Taylor, reminiscent of Zen koans:

If we are to defend ourselves against this attack, we shall have, with all respect, to correct the fundamental principle of Parmenides, to say that “what is not in a way is, and what is, also, in a sense is not.”

Is the face in the mirror a reflection of your face,

or is your face a reflection of the face in the mirror?

Chiasmus 404

Children gradually realize that their confusions of time with spatial trajectory contradicts their own experience . . . and they give up spatialization; philosophers, while they are fully aware of the same contradiction, retain spatialization and deny experience—and are even proud of it! — Milic Capek

Luke 5:2-11 shows the following chiasmic pattern —

A : (5:2) Boats—the fishermen are washing their nets

B : (5:3) Jesus teaches the people

C : (5:4) Jesus’ command

D : (5:5) No fish

E : (5:6) The miraculous catch

D’: (5:7) Abundant fish

C: (5:8-10a) The disciples’ reaction

B’: (5:10b) Jesus commissions Peter

A’: (5:11) Boats—the fishermen leave all to follow Jesus.

Chiasmus M.A.

Two by Hegel:

In the first place then, Exterior is the same content as Interior. What is inwardly is also found outwardly, and vice versa. The appearance shows nothing that is not in the essence, and in the essence there is nothing but what is manifested.

Being, the indeterminate immediate, is in fact nothing, and neither more nor less than nothing. Nothing is, therefore, the same determination, or rather absence of determination, and thus altogether the same as, pure being.

Chiasmus PhD

西 (West) Alfred North Whitehead

In “God and the World,” the closing chapter of Process and Reality, Whitehead presents a chiasmic litany to the ultimate complementarity of the world and God:

It is as true to say that God is permanent and the World fluent, as that the World is permanent and God is fluent.

It is as true to say that God is one and the World many, as that the World is one and God many.

It is as true to say that, in comparison with the World, God is actual eminently, as that, in comparison with God, the World is actual eminently.

It is as true to say that the World is immanent in God, as that God is immanent in the World.

It is as true to say that God transcends the World, as that the World transcends God.

It is as true to say that God creates the World, as that the World creates God.

These six uses, and the other fifteen in this short chapter, suggest that Whitehead uses chiasmus more as a figure of thought than as a figure of speech. This would go a long way toward explaining why so great a concentration of chiasmi occur in the concluding chapter of Whitehead’s magnum opus.

東 (East) Zen Master Dogen

Although Dogen, the founder of Soto Zen in Japan, lived and flourished more than 700 years ago, a case can be made that we are still learning to be his contemporary. Some of the most cunning (and kenning) of chiasmi come from his lips.

And so four timely examples by our wily Zen master:

Time is already none other than beings,

and beings are all none other than time.

As it is already realization in practice, realization is endless;

as it is always practice in realization, practice is beginningless.

The Way, called now, does not precede activity;

as activity is realized, it is called now.

A full being-time half known

is a half being-time fully known.

In Master Dogen’s magnum opus, Shobogenzo, I have so far found more than 250 (yes, 250!) expressions of chiasmus.

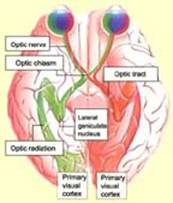

If Dogen and Whitehead found it necessary to use the rhetorical figure of chiasmus, over and over again, to express some of their insights—this made me stop and wonder whether the form of chiasmus might be related to some crosswise forms found in the structure of reality. A browse of the Internet then revealed that chiasm is the name of an X-shaped structure in the hypothalamus where the optic nerves intersect or “cross” . . . and, in the science of genetics, there is a crossing-over process, also called chiasm, in the division of cells called meiosis.

The Optic Chiasm

Furthermore, the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty uses chiasm as a technical term to refer to a reversibility whereby we humans, by means of our bodies, our flesh, can both see and be seen, listen and be heard, touch and be touched.

Variations on the Chiasmic Theme

In the Introduction, I wondered whether chiasmus, as a formal pattern, might be expressed in other crosswise forms found in the structure of reality. I found several such forms, which I reported, and the similarity was striking. In my continuing explorations, examples of chiasmic structures keep turning up all over the place.

But there was one that I found so uniquely pleasing, which expressed the very spirit of chiasmus with such clarity, that it was, for me, an epiphany.

Back to Bach

If you have ever paused by a river or lake to watch a crab in shallow water, you were probably impressed, and maybe amused, by how fast a crab can move—backwards!

There is a type of musical composition, known as the “crab canon,” that is so named because of the crab’s capacity for revving it up in reverse. What makes a crab canon unique is that two “voices” play the same theme, at the same time, but in opposite directions—with one starting with the first note and ending with the last, as the other starts with the last note and ends with the first. But, in such a case, who can say which is which?

Indeed, it has been suggested that the score for a crab canon should be printed on a Möbius strip, a slender strip of paper that has been given a 180-degree twist, and the two ends then pasted together, to form a loop that has only one surface and neither beginning nor end.

A famous crab canon was written by Bach as part of A Musical Offering, a composition dedicated to Frederick the Great, king of Prussia, after a visit to Postsdam in 1747 when the “Old Bach” regaled the royal court with amazing improvisational ingenuities at the keyboard.

More Variations

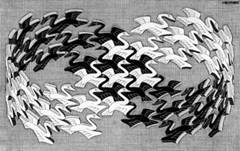

Here’s an ingenious Möbius strip by the graphic artist M. C. Escher that also trails clouds of glory representing chiasmus, infinity, transformation, yin and yang . . . the list is long.

The structure of the crab canon resembles another chiasmic structure, the palindrome: a word or sentence that reads the same forwards and backwards. An example (from Eden) is Adam’s first words to Eve: “Madam, I’m Adam.”

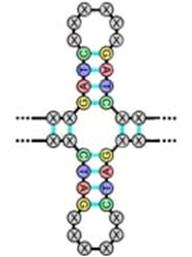

This may seem trivial but it becomes quadrivial when we learn that palindromes turn up in DNA molecules as the following picture reveals:

A, T, C, and G stand for Adenine, Thymine, Cytosine, and Guanine, the four nucleotides that form the paired strands of DNA. Like monogamous couples, A always pairs with T and C always pairs with G.

If we let the Greek letter chi ( X ) indicate a chiasmic structure, then, for DNA —

GATC X CTAG

Deriving from quad-, “four” and via, “way or road,” quadrivial is a Joycean word that Jung would have appreciated since both writers were, like fours truly, aficionados of what I call Meta-Fours. The word brings to mind a crossroads, four roads that intersect and lead in four different directions. Pointing also in four directions, and with the same symbolic suggestiveness, is the Greek letter chi, whether in its lower- (χ) or upper-case form (X).

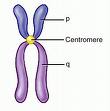

Chi (X) is suggestive not only of crossroads, but also of the X chromosome, pictured below, wherein recombinations, or crossings, of genetic material take place, one of the sources of creativity in the evolutionary advance of nature.

Since X is a symbol for Christ, this is cause for wonder whether chiasmic structures might be found here and, indeed, it turns out there are several interesting crossings:

Noting that Jesus (Yeshua) is a Hebrew name while Christ (Xριστος) is Greek, when the early Christians christened Jesus as Jesus Christ, they achieved a chiasmic crossing of Hebrew and Greek. And so we have that and other crossings—

Jesus Christ

X

Hebrew Greek

human X divine

word X flesh

λογος X σαρξ

alpha X omega

Substantial parts of early Christian teachings can be found in letters: the letters attributed to St. Paul that constitute 13 of the 27 books of the New Testament. However, in light of what we have just seen, much of Christian teaching can be found in one single letter—the Greek letter chi ( X ).3

Notes

1. My definition of “chiasmus” derives from that of Sheridan Baker in his book The Complete Stylist.

2. The adjectival form of “chiasmus” is chiasmic while the plural is chiasmi. For the science or study of chiasmic structures, I have coined the term “chiasmology,” and the “chiasmologist” is one who studies such structures. The fact or presence of chiasmus I call “chiasmicity.” For pronunciation, the chi in chiasmus rhymes with eye: ky-AZ-mus.

3. For the Christian chiasmic connections I am indebted to Philip Kuberski and his essay “Joycean Chaosmos and the Self-Organizing World,” especially his idea that “Christ’s story can be found in a Greek letter,” although it was my idea to pair it with Paul’s letters, thus enabling an epistolary pun and another crisscrossing of concepts.

HyC