As a freshman many years ago, I went off to Park College, idyllically situated on hills overlooking the Missouri River just north of Kansas City. It was there I had my first opportunity to visit a world-class museum: The Nelson Gallery of Art. On that auspicious day I found myself pausing many times before the paintings to stop and wonder, wonder in two senses of the word: sheer aesthetic wonder at the beauty of the paintings, and a more philosophic wonder that wondered about the meaning of what I saw. Philosophy, Plato says, begins in wonder.

As a concrete experience, these two senses of wonder were not separate and yet they were not the same. As the Buddhists say, it was a case of —

Not one. Not two.

不一。不二。

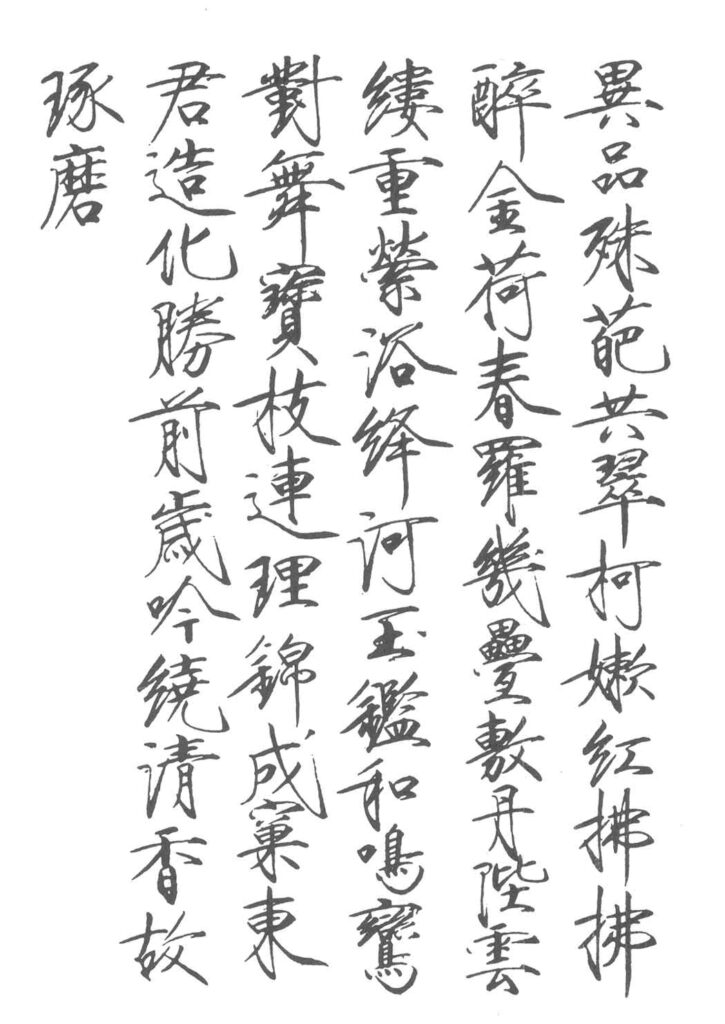

And recently, reading a book on Chinese calligraphy, when I turned a page and beheld a picture of the calligraphy of Emperor Huizong, it was an occasion to once again . . . stop and wonder. Here’s the picture:

Huizong (1082-1135) ruled as emperor of China during the Song dynasty. He developed a style of calligraphy that was pristinely new, unlike anything that came before, and he called it Slender Gold (瘦金體). His brushstrokes have been described as “floating orchid leaves,” or “bamboo moving in the wind,” or like “the legs of dancing cranes.”

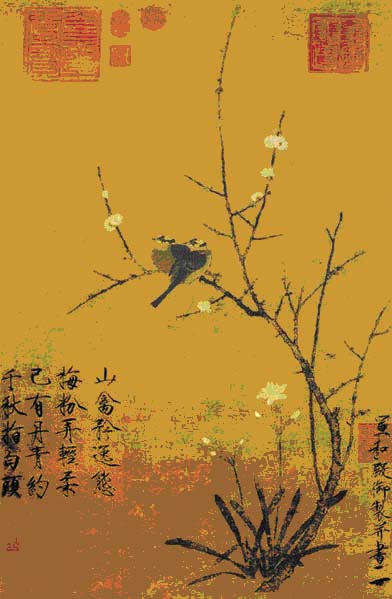

His creativity extended beyond calligraphy, for he was also a gifted painter and a poet, as his work of art, Mountain Birds, clearly shows:

Mountain Birds

山禽

Mountain Birds is the first work we know of that combines what is known, in Chinese art, as the Three Perfections: calligraphy, painting, and poetry. By combining these three in a single work, for the first time, the renowned artist-Emperor made yet another innovative contribution to his culture.

In the painting, the lines of the poem are arranged in vertical columns that are to be read from top to bottom and from right to left. Here is the text of the poem in horizontal lines that are to be read from left to right:

山禽矜逸態

梅粉弄輕柔

已有丹青約

千秋指白頭

My translation:

The mountain birds are idle, courtly, and at ease;

The rustic plum, rouged by light, is soft and supple.

With this painting comes my promise to you —

A thousand autumns more await our hoary heads.

Of the many ingenuities in this ingenious painting, note that, by perching on the branch, the birds cause the branch to bend so that the tip points to Huizong’s poem, done in his exquisite “slender gold” calligraphy. By drawing the viewer’s attention to the poem, if ever so subtly, this artistic gesture suggests that the poem plays a pivotal role. The four-line poem, a quatrain, is a hymn to love and fidelity. The two birds in the painting are definitely a pair, a couple.

“Hoary head” means the white hairs of old age. But, in what seems a felicitous touch, it also refers to the birds in the painting. If you look closely, you will see that white feathers cap the tops of their heads. This hoary-headed pair, snuggling together on the branch, mate for life, and Huizong clearly uses them as symbols of lifelong love and fidelity.

The two birds perch on a branch of the Chinese wax-plum. Huizong’s choice of this tree for his painting is far from trivial, since the tree does something quite unusual—it blooms in winter and the blossoms have a wonderful spicy fragrance. Not only is this fine symbolism in itself (flourishing even in cold adversity), it is also yet another variation on the “hoary-head” motif. The two flowers growing at the base of the wax-plum, with a single blossom and several buds about to open, further extend the theme.

* * *

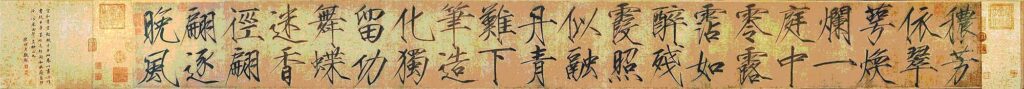

Another poem by Huizong that reveals the pristine beauty of Slender Gold is called Evening Breeze. The poem is on a scroll that unwinds from right to left. The individual characters are quite large, about five inches in height. Here’s the entire scroll, reduced in size:

晚翩徑迷舞留化筆難丹似霞醉霑零庭爛萼依穠

風逐翩香蝶功獨造下青融照殘如露中一煥翠芳

I have placed the characters underneath, in a Chinese font, for comparison. The poem begins with the top-right character (穠), moves down to (芳), then up and to the left to (依), then down to (翠) . . . and so on, moving down and up across the scroll from right to left.

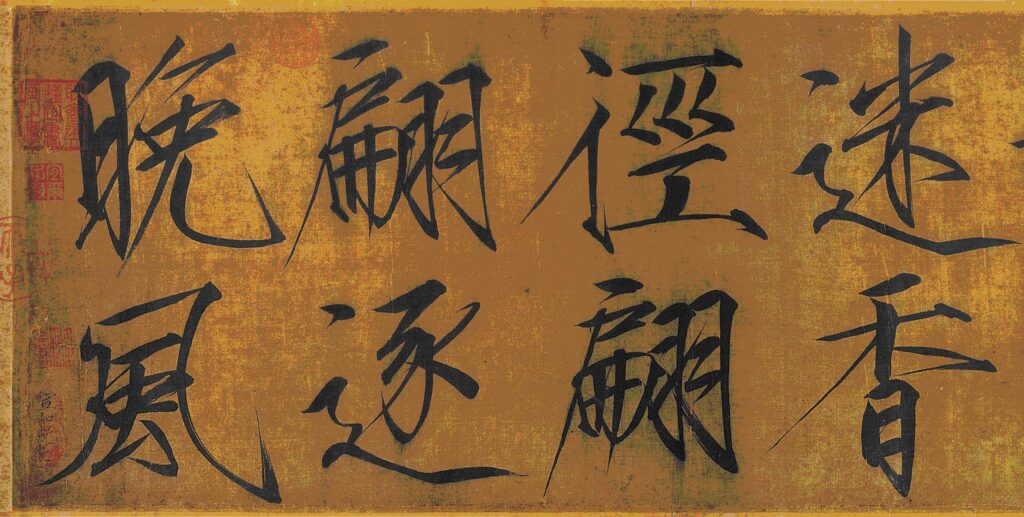

Here, in a larger picture for better viewing, are the eight characters that end the poem:

晚翩徑迷

風逐翩香

The final two characters — 晚風 — mean “evening breeze.”

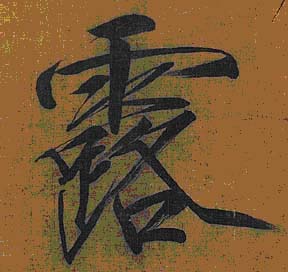

Note how the brush dances in liquid flow when Huizong draws the character for the word “dew” —

露

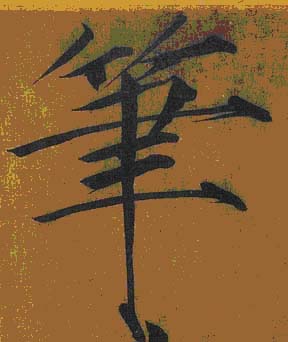

And here is Huizong’s brush brushing the character for “brush” —

筆

The first five characters of the poem, arranged in a line as in English, are:

穠芳依翠萼

Indeed, the poem consists of eight lines of five characters each:

穠芳依翠萼,

煥爛一庭中。

零露霑如醉,

殘霞照似融。

丹青難下筆,

造化獨留功。

舞蝶迷香徑,

翩翩逐晚風。

My Translation:

Boat orchids, blossoms emerald-green, fresh and fragrant;

Pervading the courtyard, their luminous presence shines,

So moist, so dappled with dew, floating in air, exultant.

On the horizon scattered clouds merge in twilight’s rosy glow.

Awash in such color, it’s hard to put down the artist’s brush,

Knowing that only Nature, and our work of creation, abides.

Ah, butterflies now, dancing in air, lost along fragrant pathways;

Flitting, fluttering, see how they flow, painting the evening breeze.

Here’s an appreciation I found online for the brushwork in this poem:

“In slender gold script, brush strokes are thin yet forceful, and the movement of the brush purposely exaggerated. Though the character forms are in regular script, the brush movement is swift and fleeting, often with a strong element of running script. In this work with the largest characters surviving from the hand of Huizong, the running script is truly outstanding.”

* * *

Over the centuries, Chinese calligraphy has become a primary art form, and an original work by a master calligrapher, whether a single character, a short poem or aphorism, or something longer on a scroll, is very highly prized and awarded a prominent place for its display in a household.

What is admired in a piece of Chinese calligraphy is not primarily the meaning, but form and movement. And that movement is both a movement of the brush and a movement of the mind. There is no coming back to do touch-ups. The writing of a character, usually with one exhalation of breath, is a liquid flow of brush and ink, and the movement comes not from a deliberate but an empty mind.

There is a Zen phrase, prescriptive of conduct in general, that exemplifies this: going ahead without hesitation —

驀直去

To conclude, I will quote from the conclusion in the book wherein I first saw beauty arising in Huizong’s Slender Gold:

“In China, anything which can claim to be a work of art has some connection, obvious or subtle, with calligraphy. The common factor may lie in the design itself or in the introduction of some calligraphic motif. Further, many forms of Chinese art have actual writing upon them—to fill awkward blanks, complete a design, or add some meaning. We frequently, for example, write poems or descriptions on pictures and sculptures, and even on walls and pillars. The smallest objet d’art bears, for preference, one or two characters.

“But we do not regard calligraphy as merely, or even primarily, an embellishment for other arts. We consider it to be itself the chief of all the arts. Without an appreciative knowledge of it, no real understanding is possible of the Chinese aesthetic.”

Chiang Yee, Chinese Calligraphy, p. 239.

Emperor Huizong

徽宗

This has been a

HyC Adventure