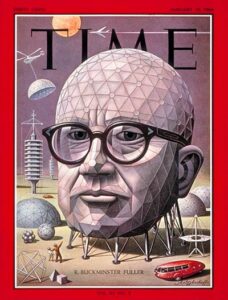

Just what is reality, and what makes for a good model of reality? One model that offers both clarity and simplicity and, upon reflection, turns out to be most satisfying, was used by Buckminster Fuller in one public lecture after another as he toured cities all over the world speaking to audiences about his new ideas.

And what is this model of reality?

The common overhand knot, made by turning a rope in two interlocking circles, thereby forming two lobes that, if pulled taut, curl up snug, one against the other.

Is the rope the knot? By no means. Imagine three ropes made, respectively, of cotton, hemp, and silk. Splice them together, tie a loose knot, and slide the three ropes through the knot, one after the other. The materials—cotton, hemp, and silk—serve only to make the knot visible. The knot itself is not material. It is, as Bucky tells us, a self-interfering pattern.

Self-interfering? In the illustration above, in the center picture, note how the two lobes, one made with dotted lines, “interfere” with each other to form the knot. Pull the knot snug, with all your strength, and it will resist exertions to be pulled any tighter.

The knot is a patterned integrity: a whole with dynamic balance of two vector forces—one directed in; the other, out. Bucky teaches us to dig wholes. And dig ourselves out of holes. Allow this to sink in for a moment.

Other wholes, such as atoms, molecules, and living cells, are knottings of energy. Take, for example, the simplest atom, hydrogen, with one proton and one electron. What is it that holds such an atom together—that is, what holds the electron and proton together, and at the same time apart, in dynamic and elegant unity? Just as in the rope knot, two complementary forces dance in measure to make the atom a patterned integrity, a self-interfering pattern. Compressive forces, pushing in, mirror the tensile forces, pulling out. The same anew for planet Earth as she orbits round the sun.

And what about us—the human knots—into, through, and out of which pass, annually, tons of food, water, and air, like so many lengths of rope, to make us visible or, should we say, corporeal? But what are we? Not a substance, surely, and surely not a thing. In a process world, as in Buddhism, there are no things.

Ernest Fenollosa: “Things are cross-sections cut through actions, snapshots.” And therefore static in a world where the reel rolls on . . .

A reiterative self-interfering pattern . . . woven with naught whatsoever. Sunyata. Emptiness.

This has been Eine Kleine Knotmusing.

HyC

This little piece owes much to Hugh Kenner (il miglior fabbro) and his magisterial book, The Pound Era.