Evolutionary theology, a new post-Darwinian way of thinking about God, proposes two ideas: first, God does not create all at once, or once and for all. God creates through a process that meanders over vast stretches of time: by evolution. And, second, rather than creating directly by divine fiat, God co-creates through persuasion or evocation—by evoking the creativity of all the many centers of power throughout the universe. To join these two ideas together, I’ll suggest a word—“evocreation”—to designate the view of how God co-creates.

What does this mean for us? Simply that God does not make us; rather, God makes it possible that we make ourselves.

As philosopher Donald Wayne Viney has pointed out, this idea began surfacing about 150 years ago, and he cites a number of notable thinkers who apparently came up with the idea independently of one another.1

1850: In a letter to a friend, Jules Lequyer wrote of “God, who created me creator of myself.”

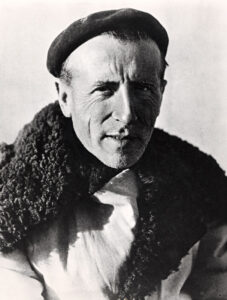

1920: The French priest and paleontologist, Teilhard de Chardin, wrote, “Properly speaking, God does not make. He makes things make themselves.”

1932: Henri Bergson, the great French philosopher, wrote of his conclusion that God “creates creators.”

Alfred North Whitehead generalizes this idea to go beyond humans and include creatures all the way down, and all the way back, to the very beginning of our cosmic epoch. Stop and think about this: to create, right from the beginning, a universe of countless creatures who are, in a significant way, creators of themselves in every new moment . . . This is the process view: God makes creatures makers of themselves. We live in a universe that is fairly crackling with creativity.

If you’re wondering how creativity is possible on more primitive levels, consider the following excerpt from an essay by biologist James Shapiro:

“The conventional wisdom about bacteria is that they are primitive organisms. Actually, bacteria are essential and sophisticated actors on the stage of life, often outwitting larger organisms for their own (the bacteria’s) benefit. Like all cells, bacteria are outstanding genetic engineers, and they have used this capacity to withstand antibiotic chemotherapy. Bacterial antibiotic resistance is one of the best-documented examples of evolution by natural genetic engineering. The discovery that genetic change results from regulated, biological processes instead of random errors and physico-chemical damage to DNA has profound implications for theories of life and evolution.”2

Notes

1. Donald Wayne Viney, “Philosophy After Hartshorne,” Process Studies, pp. 211-236, Vol. 30, Number 2, Fall- Winter, 2001.

2. James A. Shapiro, “The Smallest Cells Have Important Lessons to Teach,” in Cosmic Beginnings and Human Ends: Where Science and Religion Meet, Edited by Clifford N. Matthews and Roy Abraham Varghese, p. 205.

HyC