Frederick Amrine, a university professor who has published extensively on Goethe’s scientific works, makes what seems at first a startling observation but, once understood, it seems as obvious as a Zen koan: whenever there is progress in science, “It is not the data that change in a ‘Gestalt switch.’ Rather, it is we who change.”1 And what changes is that we develop new ways of seeing.

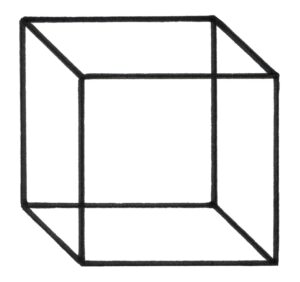

An example depicted in an early work by Picasseau will help to clarify this. When you observe the sketch below, what do you see?

There is a deliberate ambiguity built into this figure. Looked at in one way, it appears as a cube slanting down to the right. But, if you gaze at it for a while, it will suddenly do a flip and appear as a cube slanting up to the left. And so on . . . back and forth.

With sufficient practice you can make the two cubes oscillate back and forth every few seconds and, with further practice, and patience, you can even come to see the figure not as a box, but merely as lines all on the same flat plane.

The point to notice here is that the figure itself does not change. What, then, does change? As Ronald Brady, in his essay “The Idea in Nature,” explains:

“These differing configurations are not added by thought after the object is perceived but are intended by the perceiver in the act of perceiving. The observer who attempts to make the choice of cubes voluntary will find that to exchange one cube for another no further change is required than thinking (intending) the other cube. Simply look at the cube presently seen and think or imagine the alternate cube until it appears. The shift should take place in a few seconds. Only an intentional change is required to produce the difference, for the alternate cube represents an alternate set of relations rather than a new sensible report.

“The viewer makes these shifts by assigning the spatial relations to the elements in the diagram—particularly those of depth. After all, we must take the elements of the perceptual field to be at specific depths to reach this or that figure. Even the flat pattern presents no exception, for we can come to it only by seeing all elements on the same plane. Since, to see a figure, one must grasp the spatial relations of the same, seeing is also cognizing. Cognition in this sense is not a proposition about what is perceived but an activity that actualizes the perception. Each act of seeing is necessarily an act of understanding. The grasp of geometric relations that we use to understand the cube, once seen, is the same one that we use to see it in the first place. We do not perceive and then bring forward a concept to understand. We focus our understanding to bring forth a perception.”2

Notes

1. Frederick Amrine, “The Metamorphosis of the Scientist” in Goethe’s Way of Science: A Phenomenology of Nature, Edited by David Seamon and Arthur Zajonc, p. 36.

2. Ronald H. Brady, “The Idea in Nature: Reading Goethe’s Organics” in Goethe’s Way of Science: A Phenomenology of Nature, Edited by David Seamon and Arthur Zajonc, pp. 87-88.

HyC