During the Shang dynasty in China, which began some 32 centuries ago, a form of religious divination was used for prediction, and also to make things happen, such as healing of sickness and control of weather.

It was called Oracle Bone Inscription.

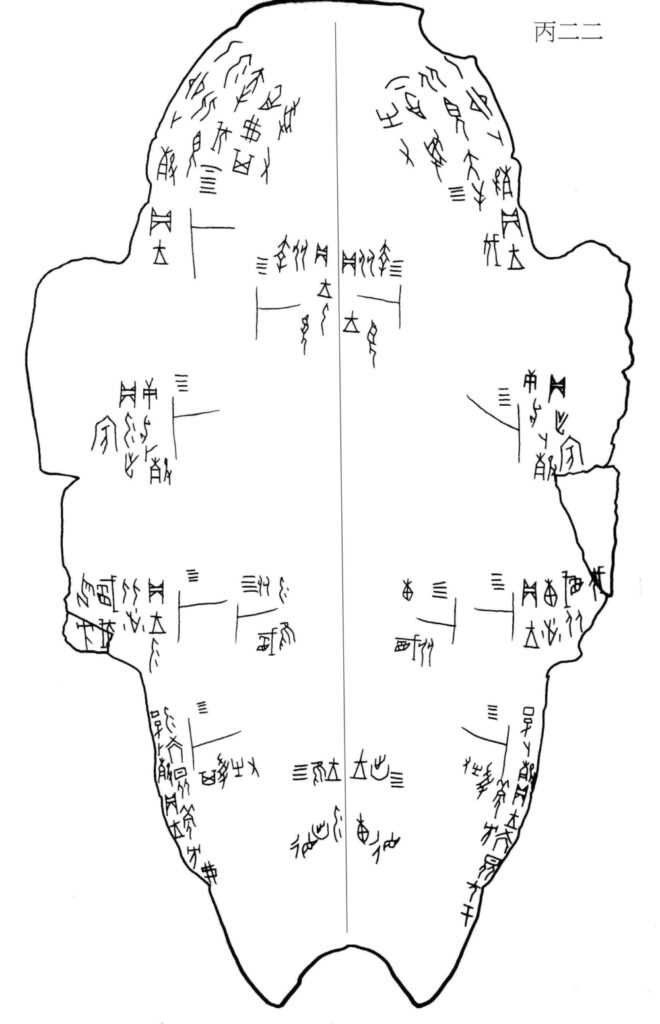

The bone of choice on which the inscriptions were incised was the flat ventral shell of a turtle, the one you see if you turn a turtle upside down. An example:

With that by way of introduction, let us turn now to positive thinking in ancient China. After discussing a controversy regarding the interpretation of an Oracle Bone, the writer goes on to say:

“One hypothesis that might be considered to account for this, is that the turtle could not say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ It only had one response, which was interpreted as degrees of certainty:

xiaoji 小吉 ‘small certainty,’

shangji 上吉 a ‘greater certainty,’

hongji 弘吉 ‘great certainty.’

“This would help to explain why one never sees buji 不吉 “not certain” as a crack notation, or why one sees bu wu gui 不牾龜 “it does not go against (the will of) the turtle,” but never wu gui 牾龜.

“It was positive thinking on the part of the Shang, that they only ascribed positive responses to the turtle, and no negative ones.”1

And there you have it.

The “crack” as in “crack notation” refers to omen cracks that were made by applying intense heat to the shell. In the illustration above, the figures that look like a capital T, rotated 90 degrees to left or right, are the omen cracks. Note that the Chinese text, in Oracle Bone Script, is inscribed around these cracks.

The Chinese character for “turtle” in modern Chinese:

龜

Note

1. Vernon K. Fowler, Contextual Hierarchies in the Shang Oracle Bone Inscriptions, p. 59.

HyC