The mind of Charles Hartshorne was of such high genius that over the course of his long philosophical career he came up with insights that are so elegant, and of such beauty, that they can be thought of as conceptual miracles. This is not to say that these miracles of thought are supernatural, rather, they are superbly natural. They accurately reflect, in a novel and singularly luminous way, what is true in the physical, conceptual, and spiritual dimensions of the natural world. Some of these conceptual constellations contribute to a robust revolution in metaphysics every bit as comprehensive as the revolution in physics. In philosophy and theology, Hartshorne’s innovations are of equal stature with the radical innovations of Albert Einstein and others of high eminence in the field of physics. With this in mind, it seems a “miracle” that they are not more widely known and celebrated.

There are a number of Hartshorne’s conceptual miracles to be discussed, but first up, and of primary importance, is his concept of Doctrinal Matrices.

1. Doctrinal Matrices

Exhaustive Sets of Theoretical Options

This innovation by Hartshorne has to do with the following question: How can we think adequately about the idea of God and the relation between God and the world until we know all the options? It was not until after his 90th birthday, after many years of reflection, that he finally solved to his satisfaction the arrangement of a 16-fold matrix that presents an exhaustive list of the formal options for thinking about God and the world—in terms of permutations of contrasting pairs such as necessity and contingency.

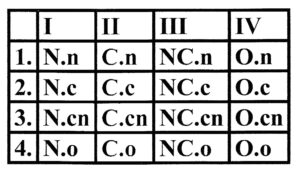

Here is an image of the matrix:

Key to Interpretation:

I. God is wholly necessary.

II. God is wholly contingent.

III. God is diversely necessary and contingent.

IV. God is impossible or has no modal status.

1. World is wholly necessary.

2. World is wholly contingent.

3. World is diversely necessary and contingent.

4. World is impossible or has no modal status.

Since, of all his metaphysical discoveries, Hartshorne felt that this was the most original and the most important, it will surely repay our efforts to understand what it means. In Hartshorne’s matrix, capital letters designate divine and lower case letters the worldly attributes. Take, for example, N.c—this means that God is wholly necessary; the world, wholly contingent. The use of capital and lower case letters (as well as the reversal of order: NC ~ cn ) symbolize the categoreal difference between God and the world.

Careful analysis of the matrix reveals both elegance and subtlety: Just as column III includes what is positive in the first two columns, so does row 3 include what is positive in rows 1 and 2. The diagonal (running from top left to bottom right) includes only those cases where the variables display a symmetrical pattern. This suggests, especially to the mathematical eye, that something significant occurs at the point where these three intersect.

To be clear on this, imagine three lines superimposed on the matrix: one straight down through column III, one straight across through row 3, and one through the diagonal running from N.n to O.o. Note the position where these three lines intersect: NC.cn—the most complex, and the most positive, of all sixteen views. This is Hartshorne’s position, the dipolar or social view of reality that he calls “neoclassical theism”—God is diversely necessary and contingent; World is diversely necessary and contingent.

It is Hartshorne’s claim that, of the sixteen possible views or positions, only one can be true. If this is accurate, then the other fifteen will all be false, with varying degrees of implausibility. The candidate for least plausibility is O.o which, as most simple and most negative, denies reality to both God and the world. If O.o is the least true of the formal options, then should not its opposite be the most true? Hartshorne argues, convincingly I think, that this is indeed the case, thereby showing that his position, NC.cn, as the exact opposite of O.o, is the one true option on the matrix.

A point to notice is that the matrix reveals far more formal options than 16. As Donald Wayne Viney, a notable Hartshorne scholar, observes, “comparable tables can be constructed for any pair of metaphysical contrasts, such as infinite-finite or eternal-temporal. For any pair of metaphysical contrasts there is a 4 x 4 table (= 16), and hence, for any two pair in conjunction, the number of formal alternatives is 16 x 16 (= 256). To generalize, if n equals the number of pairs of contrasts to be included, the number of formal options is 16n.”

As seems fitting for a cosmic leap into a new universe, Hartshorne’s matrix is light-years ahead of the what was offered by classical theism. Since classical theism is N.c, as Viney notes, “the matrix relativizes classical theism by showing that it can be construed as a truncated version of neoclassical theism,” that is, N.c vs. NC.cn.

HyC