Another feature that Whitehead found in his analysis of experience was its essential dipolarity.

Imagine pausing for a moment to look at yourself in a mirror, and become aware of the double perspective—you see your body as others see you, but you are also aware of your own inner experience. Your body, from without, is what you are as you appear to the sensory perception of others. Your mind, or inner experience, are what you are for yourself. David Griffin reminds us that this provides the basis for a distinction between mind and matter: “What we call matter is then the outer appearance of something that is, from within, analogous to our own experience.” (FC, 203)

The French paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin said that “coextensive with their Without, there is a Within of things.” And physicist David Bohm is thinking along the same lines in his distinction of two orders in nature: the implicate and the explicate.

Whitehead called these two aspects of experience the mental pole and the physical pole; hence, the word “dipolar.”

He then generalized this dipolarity to be ingredient in all actualities all the way down to the most fundamental units of nature.

Though many have tried to describe what subatomic particles look like as matter, that is, as seen from without, Whitehead was perhaps the first to try to imagine what an electron feels like from inside. To Newton’s inert mass particles, he thus resuscitated not only some interiority, but a lively inner experience with each pulsation of actuality. And thus philosopher Charles Hartshorne came to speak of how an electron can “enjoy its almost incredibly lively career of rhythmic and not too rigidly rhythmic adventures.” (BH 202)

Whitehead’s anatomy of a single pulsation reveals a beginning, a momentary phase of creative development toward a completion that ends with a thrust beyond itself into the next new pulsation. As an electron flashes along its quantum way, each tiny pulsation throbs its own actuality into existence, just as quickly fades away, and is immediately followed by another.

At the deepest level, in electromagnetic wave propagation, this same polarity is vividly exemplified in that such waves are propagated by a sheer reversal of field as a pulsation of negative charge begets positive and positive begets negative in a segue of polar reversals. In this perpetual rhythm of vivid contrasts, nature can be seen as dipolar through and through.

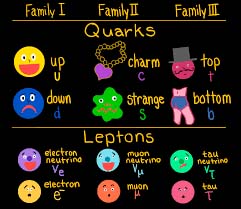

The strange, charmed, beautiful, and truly upside-down microworld of quantum physics reveals the presence of this same dipolarity, for there are two types of elementary particles, quarks and leptons, and the individual particles themselves are linked in pairs—the six quarks: up-down, charmed-strange, truth-beauty (or top-bottom in more prosaic terms), and the six leptons: electron neutrino-electron, muon neutrino-muon, tau neutrino-tau. To extend this biphasal omnipresence ever further, each particle also has an antiparticle, such as the neutrino-antineutrino pair.

Charles Hartshorne proposed that “in basic contrasts or polarities, both poles must be asserted if either is.” If this is true, and if there is life after death, as some of us believe, then we can look forward not to lives of pure spirit but to post-terrestrial careers of dipolar immortality.

Change, or the oscillation between two phases, operates at every level of reality—from subatomic particles and atoms to planets and galaxies. If dipolarity is so fundamental to the very nature of reality, what does this suggest about the nature of God?

The Divine Dipolarity

Process proposes what at first glance may appear to be an apparent paradox: that God both changes and does not change. Can any sense be made of this paradoxical proposal? The process answer is that a coherent explanation can be made by conceiving God as dipolar.

Indeed, if dipolarity is a fundamental principle, and if Whitehead is correct in holding that God can be no exception to such principles, then the divine nature must be dipolar. Moreover, not only is God conceived as dipolar, but as doubly dipolar.

One dipolarity is in terms of a distinction between two aspects of God: God’s concrete actuality and God’s abstract essence. God’s abstract essence does not change, is timeless, necessary . . . in fact, all the mostly negative characteristics attributed to God by classical theism. But as a concrete actuality, God does change, through increase of experience and value, and is temporal, contingent, and relative. Hartshorne emphasizes just how relative God is by proposing that God is the most relative of all actualities and coins the term “surrelative” to describe this. God is super-relative.

In sharp distinction to Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, God is also dipolar in how God relates to the world: both exerting influence upon, and receiving influence from.

Some critics charge that the God of process theism is not transcendent enough. To this charge Hartshorne has made a sagaciously witty reply: he said that the God of process is twice as transcendent as the God of classical theism. He was able to make this reply through his doctrine of dual transcendence. By dual transcendence, Hartshorne means that only God has uniquely excellent ways of being both absolute and relative, necessary and contingent, immutable and capable of change, and so on.

Ideal Opposites

Dipolarity is only one of many variations on a twofold metaphysical theme that weaves its way through Whitehead’s work: the unification of contrasting pairs such as the many and the one, order and novelty, permanence and change. The last pair, permanence and change, is maybe the most general expression of the underlying rhythms of process in nature. Whitehead calls these contrasting pairs ideal opposites. The point to be noticed is, that in all of these contrasting pairs, one requires the other. They cannot, in Whitehead’s words, “be torn apart.” There is an ultimate complementarity in the very nature of things, including the nature—the dipolar nature—of God.

In Whitehead’s words, “Opposed elements stand to each other in mutual requirement. In their unity, they inhibit or contrast. God and the World stand to each other in this opposed requirement.” (PR 348)

Not only do God and the world stand in mutual requirement, either one is the source of novelty, and adventure, for the other. This is the basis for Whitehead’s statement that “It is as true to say that God creates the world, as that the world creates God.” (PR 348)

In Whitehead’s scheme what appears as an opposition, or self-contradiction, is converted to a vivifying contrast. Since “all the ‘opposites’ are elements in the nature of things, and are incorrigibly there,” (PR 350) there can be no final reconciliation of permanence and change in a process universe. The world will never reach a state of static completion, and neither will God. Creation continues, forevermore and everlastingly, and so: adventure!

Getting It Exactly Backwards

Charles Hartshorne has taken Whitehead’s idea of “ideal opposites” and developed it considerably into what he calls a logic of ultimate contrasts. Consider for a moment pairs of contrasting terms such as absolute and relative, cause and effect, object and subject, being and becoming—Hartshorne calls these ultimate contrasts, or contraries. For many centuries it has been customary in theology to exalt one side of these contraries at the expense of the other—to such an extent that one side has been used exclusively as names or designations of deity. Thus we have God as Absolute, Universal, Cause, Infinite . . .

In thus exalting the absolute over the relative, being over becoming, Hartshorne argues that the medieval theologians did not get it right once and for all, but, on the contrary, they got it exactly backwards.

To illustrate his idea, Hartshorne has constructed a logical matrix (a square containing sixteen smaller squares) that reveals the structure and implications of this logic. If Hartshorne is right, then to exalt the abstract over the concrete implies that we should value objects over subjects, the possible more than the actual, and that the movement from cause through effect is a descent from better to worse, from more to less. As Hartshorne says, if this is indeed the case, then “pessimism is a metaphysical axiom.” (ZF 116)

Hartshorne considered the Matrix his most important discovery. More about this later . . .

Key to Abbreviations

FC Griffin, David Ray, John B. Cobb, Marcus P. Ford, Pete A. Gunter, and Peter Ochs. Founders of Constructive Postmodern Philosophy: Peirce, James, Bergson, Whitehead, and Hartshorne.

BH Hartshorne, Charles. Beyond Humanism.

PR Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality. Corrected Edition. Ed. David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne.

ZF Hartshorne, Charles. The Zero Fallacy. ed. Mohammad Valady.

HyC