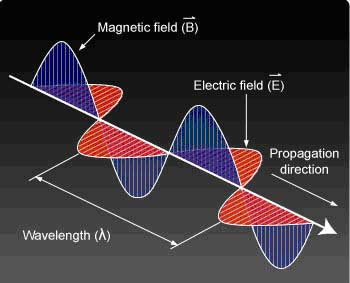

Light is an electromagnetic wave formed by the dance of two complementary pairs: an electric field and a magnetic field.

Because the fields oscillate at right angles to each other, and back and forth across the direction of wave propagation, light is a transverse wave. Transverse derives from the Latin word transversare, meaning “to turn across,” and the cross in “across” brings to mind the Greek letter chi ( χ ) and, of course, chiasmus. [If you are unfamiliar with the concept of chiasmus, see endnote 1.]

And so light does a lot of crisscrossing as it zips along at 300 million meters per second. It is somewhat staggering to try to imagine that in the one second (one second!) that it takes light to travel 300 million meters, that in that same one second it also oscillates 600 trillion times. The wave frequency of light is 6 ×1014 cycles per second. The illustration above shows only two cycles of light. Only 599,999,999,999,998 to go to fill one second.

Another of light’s many marvels is that it is self-propagating:

This chiasmic rhythm can be expressed symbolically as —

EF χ MF χ EF χ MF χ EF . . . →

What can we do but marvel at the beauty and simplicity of the path of light? Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman felt an enchantment that would last for a lifetime when he heard his high-school physics teacher say: “Light always follows the path of the beautiful.”

Light has a doubly complementary nature in that it is both wave and, at the same time, a particle, a quantum of light known as the photon.

One of the paradoxes about light is that a photon, a particle of light, has no mass and therefore no weight, and thus it may be said that a photon is “light” in more ways than one. As tiny, as diminutive, as micro-minute as it is, a photon has inexhaustible energy in that it can propagate everlastingly—witness the photons that make up the cosmic background radiation that has been around ever since the Big Bang, and is it not amazing that these particles of light wave to us all the way from the very birth of the universe itself: fifteen billion years ago! Whence cometh this inexhaustible energy in so wee a wave, in so petite a particle?

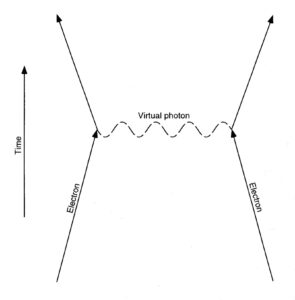

The nature of light is triply complementary because photons, like some spies, lead two lives: the “real” photons that light up the world with vibrant color and “virtual” photons that briefly pop in and out of existence as they carry the electromagnetic force that plays a central role in the structure of matter. As physicist Lawrence Fagg writes:

“QED [quantum electrodynamics] tells us that the electromagnetic force is transmitted by photons. These ‘carrier’ photons are very transient and are actually unobservable; in the parlance of the trade they are called ‘virtual’ photons.

“This is the hidden mode of existence for photons. Using the word ‘virtual’ to specify the force-carrying photons is perhaps unfortunate because it tends to imply that they do not exist, when indeed they do. Just because we cannot observe them does not mean they are not there. They are there and are a vital part of [QED] calculations; and if they are not included in these calculations, we do not get the right answer—that is, the answer that agrees with experimental observations.

“By means of virtual photons, electrons are held in orbits around the nucleus of an atom, and atoms in turn are held to each other to form molecules.

“In a carbon atom, for example, some 99.97 % of its mass is concentrated in the nucleus at its center, which occupies roughly one-trillionth of the volume of the atom as a whole. The remainder of the volume is occupied by six electrons and trillions of virtual photons transmitting the electromagnetic force that keeps them in their orbits.”2

This is a Feynman diagram showing one electron as it approaches another, interacts, and transfers momentum. The wavy line represents the virtual photon that carries the force of the interaction. At impact, one electron thus gains momentum and the other recoils as it loses momentum.

Fagg observes that, during the 15 billion years of evolution, the universe has been bathed in light on three occasions, with each occasion followed by a burst of creativity. The first came about 300,000 years after the Big Bang when the universe had cooled sufficiently for negatively charged electrons to join with positively charged nuclei to form atoms. As Fagg says, “This made it possible for electromagnetic radiation (light) to move freely throughout the universe without being trapped in constant interaction with the ionized medium of charged particles.” The legacy of this saturation of light still pervades the universe as cosmic background radiation.

Concentrations of energy gathered to become seed attractors that resulted, after a slow process taking billions of years, in stars and galaxies. “The stars and galaxies constitute the second means by which the universe is immersed in electromagnetic radiation, but over a much more extensive spectrum of wavelengths.”

As first generation stars began to collapse after exhausting their nuclear fuel, supernova explosions spewed out the “stardust” that would form second and third generation stars, some with planets. Our sun was one of those bright shining stars, and it bathed the earth with the sunlight essential for the evolution of life. And Fagg concludes, “Thus came what I see as the third stage of electromagnetism’s role in the universe’s evolution, the stage wherein the full range of its exquisite subtleties came into play.”

To these three lavings of light, I will add a fourth: During the initial moments of the Big Bang, the only elements present were light and the “light” elements—light in terms of weight, such as hydrogen and helium—so, in a very real sense, light itself, the light of the original incandescence, was the precursor of all that evolved afterward. “Omnia quia sunt, lumina sunt,” said the Irish philosopher John Scotus Erigena. Everything that is, is light.

And the Light was made Flash and dwelt among us, full of beauty and truth.

Notes

1. Chiasmus is a rhetorical figure, a linguistic twist or turn that you can use to express a crosswise mode of thought. In The Complete Stylist, p. 326, Sheridan Baker offers this definition: “Chiasmus (ky-AZ-mus) means ‘a crossing,’ from the Greek letter chi, X, a cross. You ‘cross’ the terms of one clause by reversing their order in the next.”

President John Kennedy made good use of this figure in a famous speech when he said,

“Ask not what your country can do for you,

ask what you can do for your country.”

In my book on chiasmus the concept is explored not only as a figure of speech but also, and more importantly, as a figure of thought, a figure of reality, and a figure of Deity. The book shows how the concept can be generalized beyond its literary meaning and that chiasmus, and the way it turns things around, is a powerful conceptual tool that enhances the poetics of perception.

2. Lawrence Fagg, Electromagnetism and the Sacred: At the Frontier of Spirit and Matter, 51, 52, 54, 58. The Feynman diagram appears on page 50 of the book. Quotations about the three bathings of light are on pages 124-25, in a chapter called “Electromagnetism’s Evolving Role.”

HyC