Around 1200 BCE, during the Shang Dynasty in ancient China, there arose a form of religious divination, a way of looking into the future, that is known as Oracle Bone Inscription. Various kinds of bone were used, among them the shoulder blades of oxen, but the bone of choice was the plastron, the flat ventral shells of turtles. This is the shell you see if you turn a turtle upside down. Such a turn is the first of many reversals that will be explored in this essay.

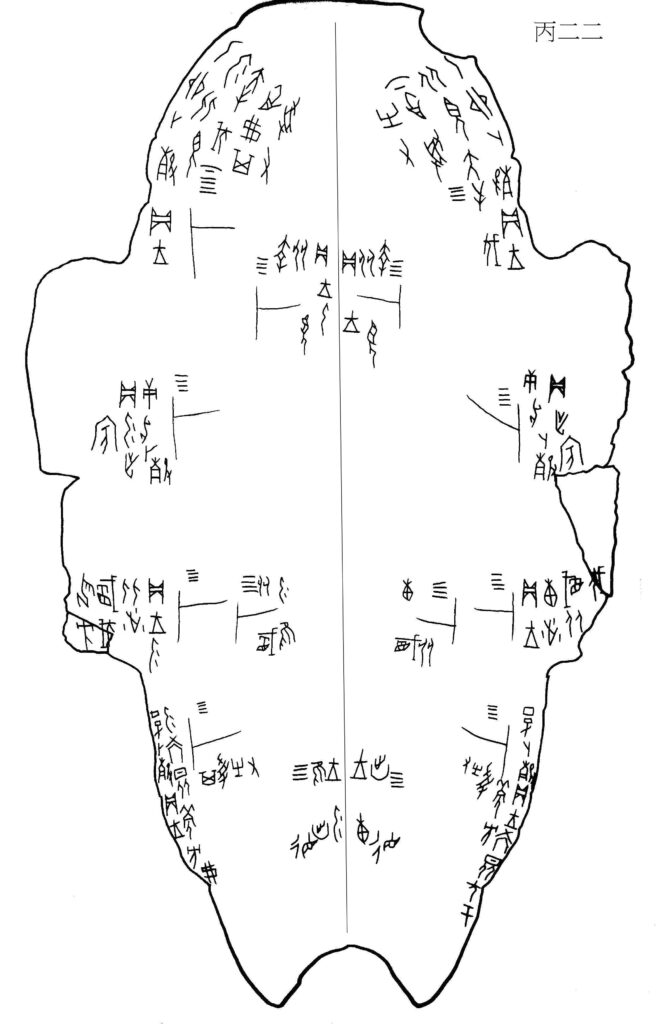

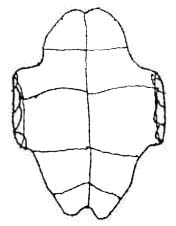

The plastron was prepared for inscription by boring several small hollows on the back of the shell and then pressing the smoldering tip of a hardwood stick to each hollow. The intense heat caused cracks on the front side that were read as omens. In the drawing of a plastron below, the several figures that look like a capital T, rotated 90 degrees either to the right or the left, represent the cracks. These “omen cracks” served as the basis for rituals of divination.

Bingbian (丙編) Plastron 22

As the drawing also shows, an early form of Chinese writing, called Oracle Bone Script (甲骨文), was inscribed in clusters around the omen cracks. This was the text, and the record, of the various parts of the divination process.

A complete divination ritual, as recorded on a plastron, consisted of several parts, with the number varying when some parts were included or omitted. But the core of the process was the “charge,” or incantation, that stated the purpose or desired outcome. This was sometimes dependent on the performance of a ritual action as in the following prayer for rain (禱雨), expressed first in Oracle Bone Script, then modern Chinese, and English translation:

片:噸蘊、窮。

貞:我舞、雨。

Divining: If we dance, it will rain.

David Keightley writes of the role of divination in Shang culture:

“Much Shang divination was concerned with forecasting the future, or with understanding the present with a view to shaping the future successfully. It seems likely, however, that the king’s production of ‘lucky’ cracks was also thought to play a magical role, so that the royal diviner did not simply forecast the future, he also helped to induce it.”1

The importance of oracle bones to the Shang can be discerned in the amount of time devoted to their production. Keightley estimates that an average of 20 hours was required for the making of each plastron. And, given that roughly 140,000 oracle bones have so far been found, this adds up to the staggering total of some three million hours that were devoted to this ritual art.2 It is also interesting to note that the plastrons were archived as records of Shang activity, making them an early equivalent of our CDs for data storage

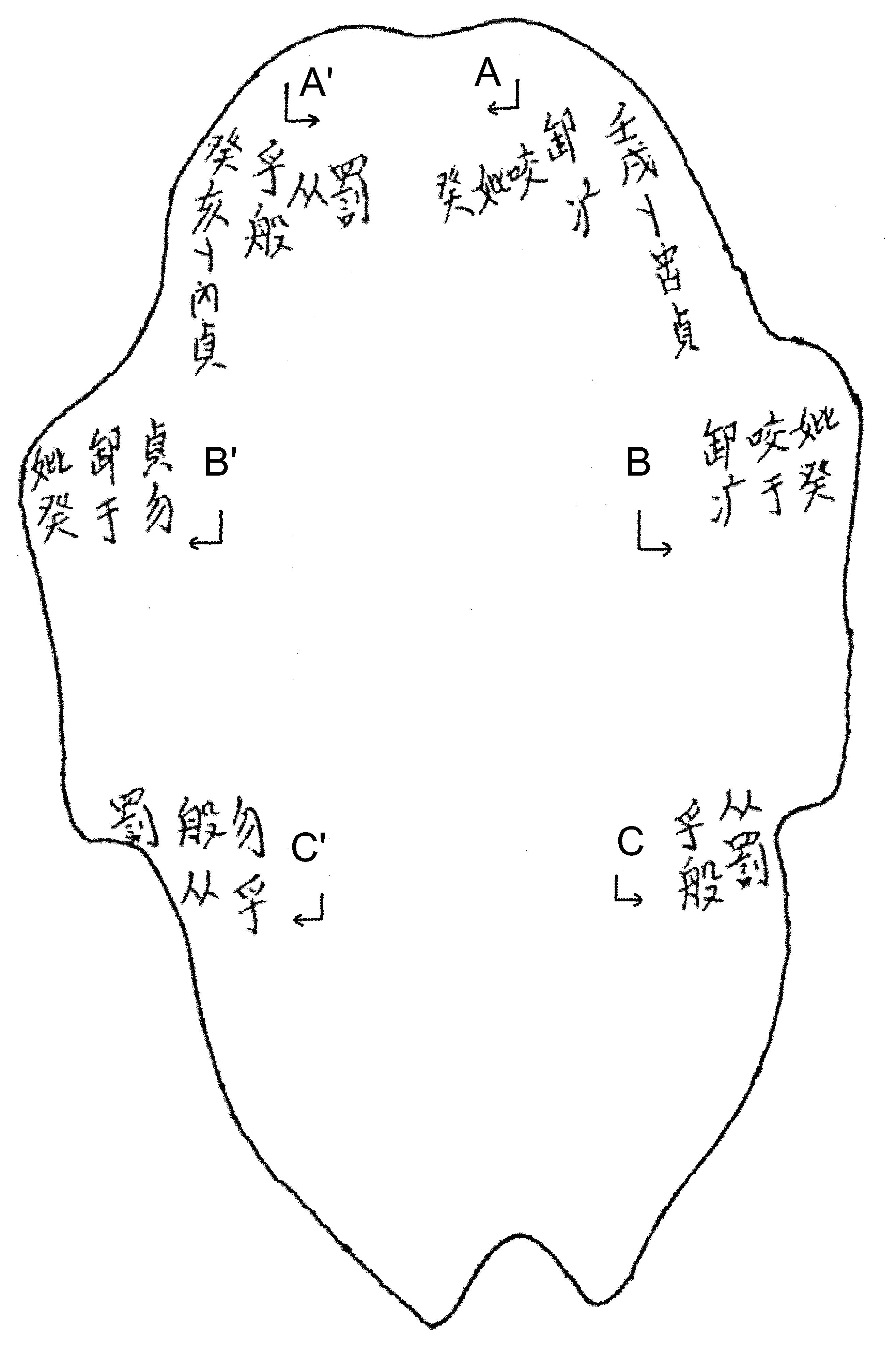

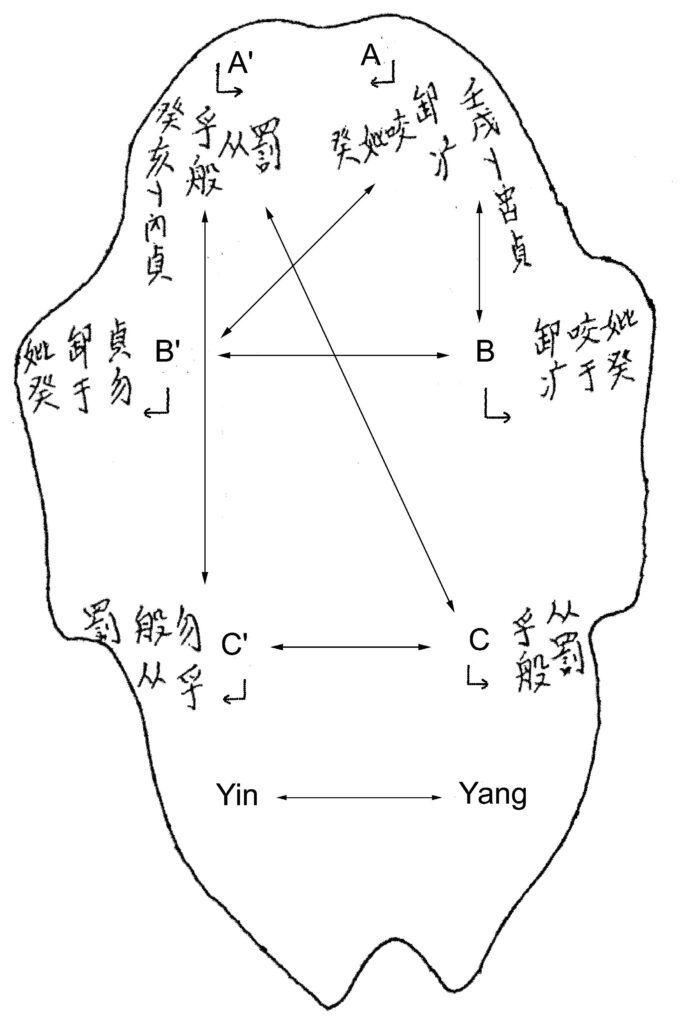

With that by way of introduction, Figure 2 shows the plastron, with the text in modern Chinese, that will be the focus of my discussion:

Plastron (Yi 4540)

Dating back 32 centuries, or 1200 years BCE, this plastron contains the earliest expression of literary chiasmus that I have so far found. Moreover, in Figure 2, chiasmus finds expression not merely once, but many times, and on more than one level.

Chiasmus, remember, is a reversal or inversion—it is the art of turning things around.3

Note that there are six clusters of Chinese characters, three on each side: (A’), (B’), and (C’) on the left, and on the right (A), (B), and (C). The hooked arrows show the direction of the flow of Chinese text; for example, A’ flows down and then to the right whereas A does just the opposite. And the reversals continue as the following table shows:

| A’→ | ←A |

| 癸乎从罰 亥般 卜 内 貞 | 癸妣咬卸壬 疒戌 卜 呂 貞 |

| ←B’ | B→ |

| 妣卸貞 癸于勿 | 卸咬妣 疒于癸 |

| ←C’ | C→ |

| 罰般勿 从乎 | 乎从 般罰 |

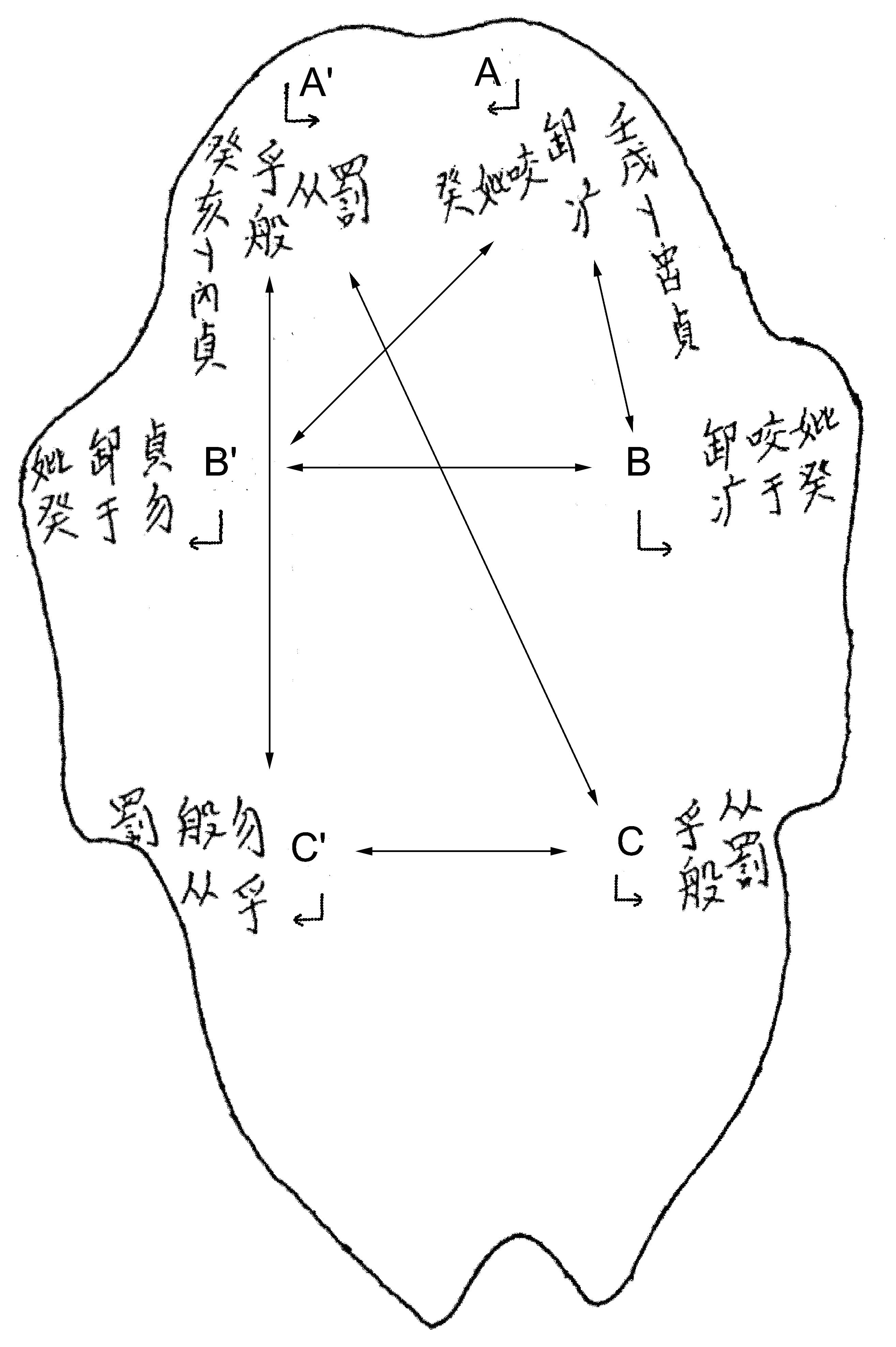

For further chiasmic twists, or reversals, let us link the six elements on the plastron so that two new triads, or sets of ABCs, are revealed. In Figure 4 below, the double-arrow lines identify, or point to, the three elements of each triad.

The first triad: A-B-B’

A: 壬戌卜、呂貞 ∶ 卸疒咬妣癸。

Crack-making on renxu day, divination by Zhong: recovery from illness by sacrificial rite to ancestral queen Gui.

B: 卸疒咬于妣癸。

Recovery from illness by sacrificial rite to ancestral queen Gui.

B’: 貞∶勿卸于妣癸。

Divination: No recovery from illness by sacrificial rite to ancestral queen Gui.

A and B are clearly a pair since they are repetitions, but they reveal their chiasmic form by a reversal in the direction the text takes: A, down and left, and B, down and right.

B and B’ repeat and also reverse direction, but with the added contrast that B is a positive while B’ is a negative statement.

B’ and A (or A- B’) is a contrast of two reversals: positive-negative and reverse directions.

A↔B, B↔B’, and B’↔A are duizhen (對貞) “antithetical pairs.”

The second triad: A’-C’-C

A’: 癸亥卜、内貞∶乎般从罰。

Crack-making on guihai day, divination by Nei: summon Ban to follow Fa.

C’: 勿乎般从罰。

Do not summon Ban to follow Fa.

C: 乎般从罰。

Summon Ban to follow Fa.

A’ and C’ stand in opposition with a flow of text in opposite directions and with one a positive statement, the other, negative.

C’ and C are also mirror images of each with the same two reversals.4

And, what’s more . . .

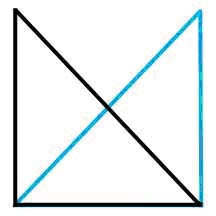

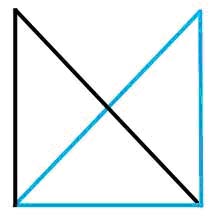

Consider the shape, or configuration, of the two triads, relative to each other, as they have been placed on the plastron. The double-arrow lines in Figure 4 show that the left triad (A’-C’-C) and the right triad (A-B-B’) form two overlapping triangles. As mirror images of each other, as reversals, the two triangles reveal a global chiasmic structure. This is clearly seen if we imagine the two triangles as the same size:

A’-C’-C highlighted in black:

A-B-B’ highlighted in blue:

And, moving up one level more, what of the plastron itself?

Where the surface itself is a natural symbol, with one side mirroring the other, this is the perfect surface, or frame, to display antithetical pairs. The plastron expresses the binary theme on a purely formal level, with no substantive content.

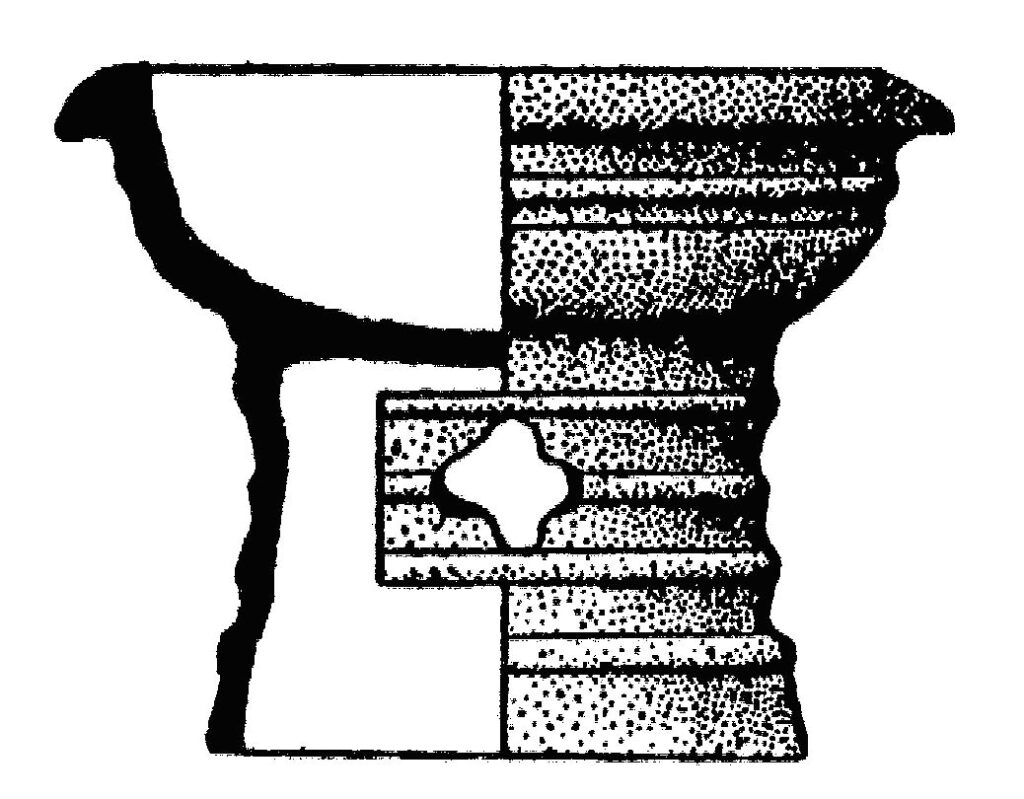

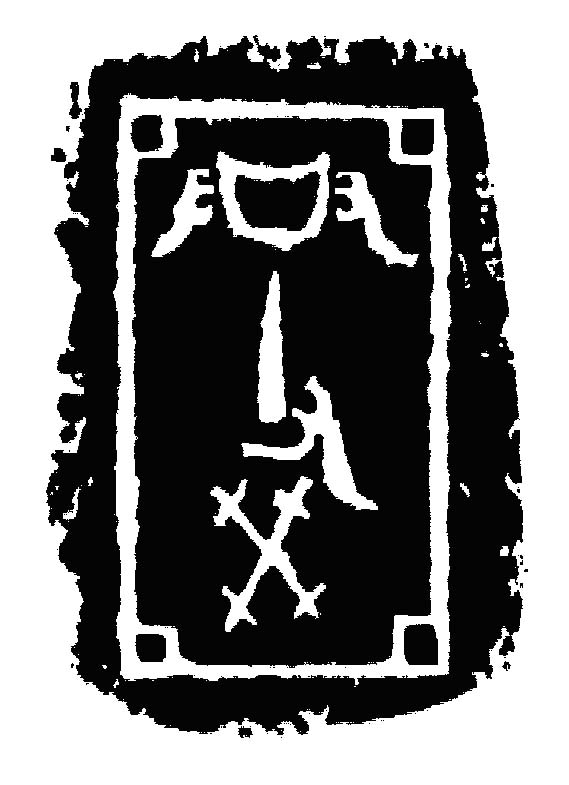

Note that the shape of a plastron is not square or rectangular, but cruciform. It takes the form of a cross. This cruciform shape is enshrined as a recurring motif in Shang ritual vessels and other works of art. It is known as the ya symbol and here are two examples:

A Dou (豆) Vessel with Ya Hole in Base

Rubbing of a Bronze Inscription within a Ya Frame

It also finds expression as the Chinese character ya . . .

亞

. . . and in the variety of forms that ya took in Oracle Bone Script:

薮鑓愉愈油癒勇

The turtle as a whole had symbolic significance for the Shang.

Since the top shell of a turtle, the carapace, is shaped like a dome, in Shang cosmology this became a symbol of the heavens, while the plastron with its flat shape was a symbol of the earth. The turtle as a whole, top and bottom, was a symbol of the cosmos.

Rubbing of Turtle Motif inside a Pan (盤) Water Basin

In Figure 10, a Shang artist has given us confirmation of this by inscribing, on the carapace of the turtle, a pattern of circles, representing stars, and thus the night sky.

For even more antithetical pairs, a chiasmic quote by Sarah Allan:

“This association of turtles with water is consistent with the species of turtle used in Shang divination, almost all of which were water rather than land species. Furthermore, the oxen which were used in divination may have been water oxen. In divination, a crack was made by applying a red hot hardwood poker to the shell or bone. Thus, in the case of the turtle, and possibly also in the case of oxen, fire was applied to water—the two primary cosmic forces identified with yin and yang were conjoined.”5

Yin and yang—yes! Just as yin and yang, as a complementary pair, as light and shade, bring to mind the plastron . . .

. . . so do the many intertwinings of this plastron bring to mind the yin-yang symbol . . .

. . . and there is now a general consensus that the antithetical pairs, and other reversals, so pervasive in Oracle Bone Inscriptions, are clear precursors of yin-yang cosmology and correlative thinking.

A summary of the many different expressions of chiasmus on this one plastron can be presented in four groups:

I

With each of the three pairs, A’-A, B’-B, and C’-C, where one flows from right to left, the other flows from left to right. See Figure 3.

II

The two triads, A-B-B’ and A’-C’-C, embody two forms of reversal: direction of text and a positive-negative contrast. See Figure 4.

III

Viewing the two triads as overlapping triangles, A-B-B’ and A’-C’-C are reversals in that they are mirror images of each other. See Figures 5 and 6.

IV

The plastron itself, with one side mirroring the other, expresses the theme on a purely formal level. See Figure 7.

It is no exaggeration to say that this plastron is fairly bristling with chiasmic structures, and not only through variety but on different levels. Like four nested Chinese boxes, the plastron includes the two triangles which include the two triads which include the three pairs.

To find so early an example of chiasmus is fortunate, but to find one that is overflowing with chiasmicity—this is auspicious indeed. I will conclude by engraving on this page an Oracle Bone Inscription of my own:

片:怏捷。噸致欧、臆。

貞:乎龜。我荻曰、吉。

Divining: summon the turtle.

I read the cracks and say, auspicious.

Notes

1. David N. Keightley, “The ‘Science’ of the Ancestors: Divination, Curing, and Bronze-Casting in Late Shang China.”

2. David N. Keightley, Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China, p. 89.

Keightley gives the details behind his estimation:

“If the diviners made one crack a minute (and that seems an overly rapid estimate), it would have taken over two hours to perform the . . . divinations in this set; if they made one crack every two minutes, it would have taken over four hours, and so on. . . . If we include the estimated ten man-hours required to clean, saw, and polish the five plastrons, the eighty man-hours required to prepare the hollows, the additional thirty minutes (at a minimum) required to crack the divinations, and the five hours (at least) needed to carve and color the inscriptions, we can see that divining this particular plastron set would have required some one hundred man-hours of specialized labor, or twenty hours per plastron. If we assume that a scapula would have involved similar effort and apply that twenty-hour figure to the total estimated corpus of 69,000 scapulas and 69,000 plastrons, we may estimate that some three million man-hours were devoted to [oracle bones] during the historical period; or, put another way, to divine 1.3 scapulas and 1.3 plastrons every day would have required about fifty man-hours a day. Crude though these estimates are—and they are probably conservative—they indicate, once again, the importance the Shang attached to the divination ritual.”

3. A refresher on chiasmus:

“Ask not what your country can do for you,

ask what you can do for your country.”

That sentence, spoken by President John Kennedy in a famous speech, is a good example of chiasmus, a rhetorical figure that reverses the terms of the two clauses that make up a sentence, or a part of a sentence.

Chiasmus is thus a linguistic twist or turn that you can use to express a crosswise mode of thought. Chiasmus (ky-AZ-mus) means “a crossing,” from the Greek letter chi, X, a cross. You “cross” the terms of one clause by reversing their order in the next.

As I have demonstrated in other essays, the concept of “chiasmus” can be generalized so that it is not only a figure of speech but also, and more importantly, a figure of thought and a figure of reality.

To be keen on chiasmus, and to ken its many forms, is to be cross-wise. :-) (-:

The Möbius strip, with its double ends joined, is a splendid chiasmic figure:

4. My discussion of the inscriptions on Figure 2 follows the perceptive analysis of Léon Vandermeersch in the essay cited in References. My English translation derives from his French translation of the Chinese text that stems from the original Oracle Bone Script.

5. Sarah Allan, The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China, p. 111.

References

Allan, Sarah, The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China.

Douglas, Mary, Thinking in Circles: An Essay in Ring Composition.

Fowler, Vernon K., Contextual Hierarchies in the Shang Oracle Bone Inscriptions.

Keightley, David N., Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China.

Ibid., The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China.

Ibid., “The ‘Science’ of the Ancestors: Divination, Curing, and Bronze-Casting in Late Shang China.”

Vandermeersch, Léon, “Les origines divinatoires de la tradition chinoise du parallélisme littéraire,” an essay in a 1989 issue of Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 is from the Bingbian (丙编) collection of Oracle Bones. Bingbian 丙编 is short for Yinxu wenzi Bingbian 殷墟文字丙编. 4 Vols. Edited by Zhang Bingquan 张秉权. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, 1957-1972.

Figures 2, 4, and 7 are adapted, with my modifications, from, “Les origines divinatoires de la tradition chinoise du parallélisme littéraire,” an essay by Léon Vandermeersch.

Figures 8, 9, and 10 are from The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China by Sarah Allan.

The Oracle Bone Script font is from the Mojikyo Character Map, courtesy of the Mojikyo Institute, online at:

http://www.mojikyo.org

Hyatt Carter, Ch.D.

Doctor of Chiasmology