About three years ago, as one of my HyC Presentations, I sent out an essay that describes the complex and beautiful structure of John’s Gospel, a structure based on the rhetorical figure known as chiasmus. The title of the essay is:

The Gospel of John: A Miracle of Composition

and I will soon be posting it on this website. The essay begins with these words:

BEGIN QUOTE

The Gospel of John, as a whole, has a five-part structure. The structure is a complex chiasmus, with an A-B-C-B’-A’ pattern, and the chapters and verses can be outlined as follows:

A: Part 1 (1:19-4:3)

B: Part 2 (4:4-6:15)

C: Part 3 (6:16-21)

B’: Part 4 (6:22-12:11)

A’: Part 5 (12:12-21:25)

The defining feature of a chiasmus is its parallel structure, meaning that if you compare A with A’, and B with B’, you will find in each pair a statement (in A) and a restatement (in A’) of the same or similar words, phrases, ideas, or motifs. Located at the center, C is the hinge or pivot on which the chiasmus turns.

END QUOTE

While I am still amazed at the chiasmic beauty of John’s gospel, I found myself “walking on air” just a few days ago when I discovered the mandalic beauty of an even deeper and more complex structure that gives luminous form to the fourth gospel.

The Gospel of John, as a vast and interconnected chiasmic mandala, is elaborated by Bruno Barnhart in his 537-page book:

The Good Wine: Reading John from the Center

Mandalas are fourfold concentric structures that express unity-in-diversity or wholeness. The great Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung was very keen on mandalas, and they play an important role in Eastern spiritualities. An example that shows the typical wedding of fourfold and circular themes:

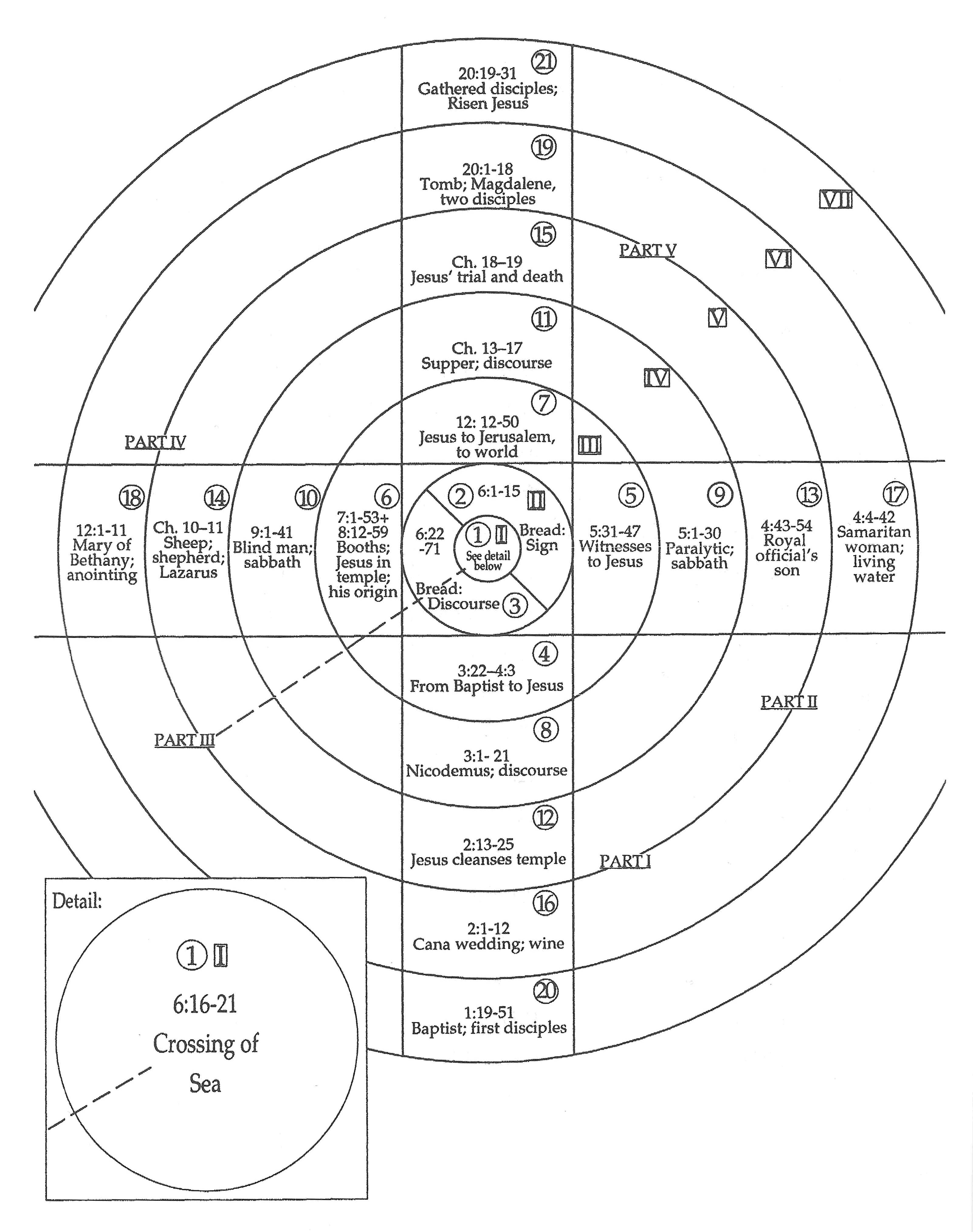

With this in mind, here is a schematic showing the chiasmic mandala that Barnhart has discerned beneath the surface of the fourth gospel:

This is mandalic form speaking from the depths of the Gospel of John.

Barnhart arranges the Gospel in 21 sections, (the numbers enclosed in circles in Figure 1.5), and arranges them on vertical and horizontal axes that yield the shape of a cross. A mandalic reading of the Gospel begins in the center, with John 6:16-21:

“When evening came, his disciples went down to the sea, got into a boat, and started across the sea to Capernaum. It was now dark, and Jesus had not yet come to them. The sea became rough because a strong wind was blowing. When they had rowed about three or four miles, they saw Jesus walking on the sea and coming near the boat, and they were terrified.

“But he said to them, ‘I Am; do not be afraid.’

“Then they wanted to take him into the boat, and immediately the boat reached the land toward which they were going.”

Barnhart comments: “The ultimate center of the pattern is taken to be the ego eimi or ‘I Am’spoken by Jesus in 6:20. This expression evokes the divine name; Jesus is the creative Word that was ‘in the beginning’ (Prologue, 1:1), who appears now, moving like the Spirit over the waters of the primeval chaos of Genesis 1:1. This divine Word, source of all creation (1:3), dwells at creation’s center and regenerates it in himself.”

The seven rings in Figure 1.5, beginning with the night sea-crossing in the center, represent the seven days of the “new creation” inaugurated by Jesus, which Barnhart subtly correlates with aspects of the seven days of the “first creation” described in the opening chapters of Genesis. In both cases, as well as in the baptism of Jesus, “I Am” is there upon the face of the waters.

The Johannine mandala reveals many correlations that might otherwise be missed. For example, note the four events that constitute Day Six: sections 16,17,18, 19. In each of these we see Jesus interacting with a woman and thus Barnhart calls this the Feminine Ring of the mandala, or the Day of Woman. The motif of water also figures in each of these four sections: water and the good wine, water at the well of Jacob and living water, the fragrant oil of anointing, and the tears of Mary Magdalene.

Barnhart on the Sixth Day:

“On the sixth day of creation, our gospel opens out into a fullness, a more perfect symmetry, a four-petalled blossoming of the symbolic language of John. These four episodes are more intimately related, and more nearly approach a single image, than do the episodes of any of the other days. It is as if the gospel had suddenly come into focus and its overall symmetrical structure had become apparent all at once.

“The four Jesus-woman narratives may be seen as the four poles of the mandalic figure, so that the women represent the height and depth, the length and breadth, so to speak, of the Christ-event. We shall see more precisely how both the intensive or unitive dimension, and the extensive or anthropological-social dimension, are represented by these four women. The four women whom Jesus encounters, then, encompass the whole of humanity with all its possibilities. They are, together, the one bride of the Word.”

And that bride is Sophia, or Wisdom, the Divine Feminine that is one with the good wine of Cana.

“Again, the true bride and the wine are one. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the creature, the woman, in whom the wine of Sophia becomes incarnate, becomes flesh and blood, then to remain in the world as church, body of Christ. This sophianic wine, the divine-human Feminine, is the inner music of John, a golden thread which has remained almost entirely concealed throughout the subsequent history of Christianity—shining out for a moment from time to time from within the more sapiential currents of our tradition.”

“Woman, in Christ, becomes the bearer no longer of the deadly fruit but of the living water, the oil of immortality, the wine of union which corresponds to her own nature, her very femininity. And thus it is once again ‘through woman’ that Christ comes into the world this second time, at his resurrection. It is through the interior femininity of the human person, that unitive interiority of the person, that the divine Unitive (i.e. divine Feminine, or Holy Spirit) enters into humanity and creates it anew. It is through the fourfold river of the interior feminine that the new life flows out into all the world. This is the meaning of Cana and of each of the ‘woman’ episodes of the sixth day.”

“The water, that feminine unitive that lives within every human person, is stirred at the approach of the Messiah. It is he who is anointed with the unitive divine Spirit, and who promises to impart that same Spirit, the living water. The water of human life reddens at the approach of its destiny as wine.”

“The movement from Word to Spirit, from a largely dualistic ‘masculine’ revelation of God to the interior ‘feminine’ and unitive revelation (or self-communication) of God, is expressed with incomparable power and subtlety in John’s gospel. This dramatic transition can be seen as the hinge, the pivotal center, of the entire biblical history.”

To miss all this is to turn the wine, the good wine, back into water.

She is sunrise in the blood,

Sweet inner resurrection.

Some other correlations:

“The wine which Jesus brings forth at Cana flows directly from the piercing of his side upon the cross, and the issue of blood and water.”

Sections 9 and 10, in mandalic symmetry, feature healings, both with a sabbath motif, while another pair, 13 and 14, are stories of raising from the dead.

The two axes that form the cross have stories to tell:

“Episodes on the vertical axis develop the gospel’s central thematic of Jesus’ self-revelation against the background of the institutions of the old Israel, and then in the midst of his own disciples. Along the horizontal axis, on the other hand, the focus broadens to embrace Jesus’ public ministry of teaching and of healing. The scope of the narrative here is more pastoral, more anthropocentric.”

Also, the lower arm (old order) of the vertical axis (20-16-12-8-4) contrasts with the upper arm (new order), and the right and left horizontal arms have symbolic roles.

“The bread which Jesus dips and hands to Judas (13:26) seems a dark sacrament, ironic counterpart to Jesus’ self-communication to the disciples through his institution of the eucharist in the synoptic supper accounts. ‘After he received the piece of bread, Satan entered into him’” (13:27).

“The tears of this woman [Mary Magdalene], who is full of sorrow, are the water which is symbolically transformed into wine. This wine is what we shall see being poured into the disciples in the next scene in John 20: their baptism with the Holy Spirit, the in-breathing by which they become the body of Christ, the new Adam, through his sophianic presence within them.”

Much more could be said (the book runs 537 pages) but let us end with a quote from my essay on the Gospel of John and, finally, one by Barhnart:

Such consummate artistry suggests a level of inspiration that, in itself, inspires wonder. Some icons in the Greek Orthodox tradition, ones that evoke a special reverence, shine with such spiritual splendor that they are said to be acheiropoieta (Greek αχειροποίητα), “not made by the hand of man.” The structure of the Gospel of John is of such elegance, and such depth, that it too seems a miracle of composition.

“We gradually discover in his gospel hidden paths of symbolic imagination of an audacity and reach that astonish us, and that are sealed to the mind which refuses to step off the well-marked path.”

HyC